Today’s piece is part of a series on Fatherhood from a group of men writing on Substack that includes

, , , , , and me. You can find all of the pieces from the series in this introductory post.When I was twelve years old my life profoundly changed in an instant. I just didn’t know it then.

It was a time when baseball was my obsession. My biggest concern in the world was how well I performed in my Little League games. I followed professional baseball religiously too. I would wake up, get ready for the day, head downstairs for breakfast, and flip open the morning paper to devour the box scores, stories, and stats. On any given day, I could tell you that day’s top ten leaders in batting average, home runs, and earned run average, for both the American and National Leagues.

The team I played on was called the Yankees and so, naturally, I followed the professional Yankees team closely too—in addition to following both local Bay Area teams, the Giants and A’s. I loved the rich history of the Yankees (before I knew—or cared—about their rich salary payroll). I remember doing a report on a book about Mickey Mantle for school. And then later I read another book about Roger Maris, the guy who broke Mickey Mantle’s single-season home run record, when he hit 61 of them in 1961 (a stat that has stuck with me all these years).

I can’t tell you how many times I watched the films The Natural and Field of Dreams. After each viewing, I’d be more and more inspired to hit the field and practice again.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I wanted to be a pro ballplayer when I grew up. At the time, it wasn’t too far-fetched of a dream. I mean, I was one of the top players in the league and routinely made the All-Star team as one of the best pitchers on the squad. And for a long time, I knew I was one of the best ballplayers in my corner of San Jose, California. My confidence was riding high.

Being a baseball player was nearly my entire identity at that young age.

But there was a moment when a chink in my armor of self-confidence was formed.

It was a sunny, mild spring day and I was at the plate in the middle of a typical mid-season game. I don’t remember the score. Or if there were any runners on base. But I remember there was nothing big on the line. It wasn’t the end of the game with my team needing a big hit to score a run to tie or win. It wasn’t a playoff game or anything like that.

My at-bat ended with a swing and a miss for strike three. I didn’t think much of it and headed for the dugout. But then I heard my dad in the stands say, “C’mon Lyle!” Not in a jovial, encouraging, uplifting tone. But in a disappointed, judgmental, and by-missing-that-pitch-you-have-embarassed-our-family-name sort of tone.

When I close my eyes and relive that moment, I feel that little boy shrink into shame. He wants to curl up in the corner of the dugout and cry. But he would be mortified if he cried in front of his team. A second later, he’s angry. Angry at his dad for the overly harsh tone. Then he tries to rationalize his failure. Big leaguers strike out all the time, he thinks. If they are successful ⅓ of the time in their career, they’re a shoo-in for the Hall of Fame. He doesn’t know what to do with this onslaught of varying emotions in such quick succession. Instead of letting his emotions flow through him, he grabs his mitt, trots out onto the field, and suppresses them all.

And he’s been suppressing them ever since.

If my dad were alive today, I’m sure he would defend himself and say he didn’t mean any harm. He’d say it came from wanting me to be the best I could be. But more than likely, he probably wouldn’t even remember it.

Nowadays, I know more than he did about challenging topics like patriarchy, toxic masculinity, and societal expectations—whether explicitly said aloud or not—that men remain stoic and not show outsized emotion. But these topics weren’t openly talked about in the late 80s.

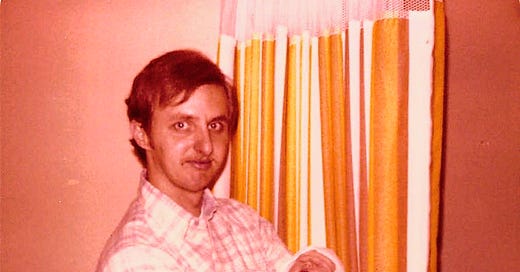

Back then, my dad was running on his own scripts—ones I can only guess from knowing the man for over 40 years.

He was raised in a home with an alcoholic mother and father, both of whom were also chainsmokers. From stories I heard over the years, they didn’t have much money and they didn’t show much affection either. When my dad was a little boy, it must have seemed like they loved their vices more than they loved him.

And so he figured out how to fend for himself. He started working at a young age to be able to afford the things he wanted. He voluntarily enlisted in the Army to serve his country during Vietnam, but also to learn how to fly helicopters on the government’s dime, instead of being drafted and sent into the sweltering jungle with an assault rifle hanging from his shoulder hoping he didn’t step on a landmine.

As he got older, met my mom, and started a family, he was determined to provide a good life for us. He sold real estate, a career that appealed to his entrepreneurial, pull-yourself-up-by-your-own-bootstraps mentality, allowing his hard work to be congruent with the amount of money he could make for our family (as long as the markets cooperated). A large part of his identity was tied to his work. It made him feel knowledgeable, helpful, and proud that he could readily provide for us, simply with his intellect.

Reflecting back on that moment when he said those words to me from the stands, I wonder if my success was part of his identity too. Or, more specifically, I wonder if my lack of success threatened his identity as a successful man and father.

Perhaps it’s unfair of me to dwell on this single phrase said at a moment when he wasn’t at his best as a father. Maybe he was stressed about a client at the time. Or simply hungry. Who knows.

Fair or not, the truth is that the phrase “C’mon Lyle!”—along with that biting tone of voice—is a script that’s been playing on repeat in my head ever since.

It lives in the darker, shadowy parts of my psyche. It mostly manifests as self-criticism and shame. But it has also come bursting out of me in a fit of self-harm more times than I care to admit. The script plays when I make a mistake, especially when I think I should be able to master whatever it is I’m attempting to do. From saying something that causes a disagreement with my wife to hitting a bad golf shot, and even something as innocuous as filling my daughter’s meds incorrectly. The voice is always waiting, ready to berate me at the slightest provocation. I’ve been unconsciously attempting to squash it down all these years but that only causes it to fester and grow until it ruptures in unhealthy and unhelpful ways.

Instead of ignoring it and hoping it goes away, I’m actively working to unravel and rewrite the script through somatic, emotional, and relational work. I’m bringing the harsh inner critic out from the shadows, facing it, and just sitting with it and letting it wash over me. The work can be exhausting. And yet, the script has less power in the light. It won’t disappear. It will always be a part of me. And it’s okay that it’s there. It can’t hurt me when I recognize that it exists.

I’ve sometimes wondered what my life would look like had I not heard those words from my dad. I don’t think I would’ve become a professional baseball player. I didn’t have enough natural talent. And work ethic can only get you so far when 99.9% of people don’t make it to the upper echelons of a sport. But maybe I could’ve had slightly more confidence. Maybe I could’ve been a little nicer to myself. Maybe I could’ve spent less money on therapy. What’s more probable is that the voice still would’ve weaseled its way into my shadow by some other means. It can’t be completely my dad’s fault. I have some culpability in it too.

It wasn’t all bad. My dad also instilled positive lessons in me. I learned the value of an honest day’s work. I learned the power of generosity. I learned the honor of loyalty. He provided me with an invisible safety net that allowed and empowered me to pursue ambitious goals. I’m grateful for all of the good things he passed on to me.

As I reflect on myself as a father and stepfather, I want to show up as a thoughtful, intentional, and caring influence. I want to push my daughter and stepdaughter to be the best they can be at whatever they set their minds to. Yet I don’t want to become too attached to the outcome. Because the outcome I want is irrelevant.

The more time I spend letting my toxic tendencies mindlessly run the show, the less likely I’m able to show up like I want to.

They will no doubt develop their own scripts in their lives—both negative and positive.

We all do.

And as a father and stepfather, it’s inevitable that my fingerprints will be smudged on their scripts somewhere. My hope is that they look upon my prints fondly when I’m gone, like artifacts to preserve and pass on, rather than something they spend a lifetime trying to erase.

If you enjoyed this piece, go read the other pieces from the Fatherhood series.

And when you’re done, could you please let me know that you enjoyed mine by giving the heart button below a tap?