The part of San Francisco where we lived when I started middle school was right in the geographic center of the city, a mix of of stately captain’s homes, time-worn Victorians, and working-class four-plexes, grey in the seams and lit in the early mornings by the gentle pulse of the old Coca-Cola sign on the downtown horizon. My memory of the city in those years still has daylight in it, but the colors are muted like photos of those times. My parents were both working and doing well enough that they’d bought a big place on a double lot on the corner of Hill and Sanchez, and my father would stand on the deck overlooking the southern part of the city and practice star sights with a sextant, dreaming of taking off to sail the roaring forties. My world was much smaller, limited to the few blocks I knew from my paper route and sometimes down to 24th street, still taking the big hills sitting down on my skateboard like a little kid.

Perhaps in part due to their success at work, their marriage had begun to unravel, and that, combined with the double-digit mortgage rates of the time, meant that they couldn’t afford to keep sending me to private school. That very special place that I used to take the school bus to every morning only ran through fifth grade anyhow, and so many of us kids that went there had tested so far above our grade level, that it seemed to make sense for me to skip ahead at the end of fourth grade and start sixth grade a year early.

I showed up at Everett Middle School in the fall still wearing my same football jersey and brown corduroys from fourth grade, a little kid amidst an older, bigger, and much more diverse public school population. My parents had given me half of the converted downstairs as my room—and I made sure to keep the basement door tightly shut, as I was still very afraid of the dark back corners that reached up under the old house.

At my new school I found myself way ahead of the math teacher as she tried to explain the simple geometry of a rectangle and yet very much behind the waves of pre-teen kids crashing around the high-fenced prison yard outside. Real sex was in the air—tight jeans and ESPRIT tops, lip gloss, LeSportsac purses, roller skates and Fast Times at Ridgemont High—and I was unprepared. At first I put my energy more and more into the fantasy worlds that I’d already been deep into in third and fourth grade—the adventures of Tintin and the Advanced D&D Dungeon Masters Guide led directly to a dresser drawer full of glossy 80’s porn, bulging with issues of Hustler and Oui that I’d snake from the corner store that I passed every morning on my paper route. Those intensely captivating images took me further and further away from the reality of what was happening at school, and yet also made it just possible for me to believe that the girls in the halls would all soon reveal that their sixth-grade daydreams were as triple-X-rated as the so-called letters that I loved reading in my stash of adult mags.

That first year at Everett was tough. My parents were busy and distracted, and I found myself in the deep end, all alone. School was easy—too easy—and the environment was a major downer compared to where I’d been going before. Jumping from fourth grade into the first year of middle school I found myself no longer in the beautiful, historic and inspiring surroundings of the Crocker Mansion and now, instead, locked up in a place seemingly purpose-built to make you think of escape, with thick walls, high fences, and a klaxon sounding on the hour.

I started to skip out however I could, going over the fence to buy Funyuns and Dortios at the corner store down at 18th and Church, or through the back of the library and up the stairway to the roof, where I’d try to make sure not to get spotted by any adults while at the same time hoping to be seen by my friends down in the yard. School was no longer a place of learning about Ishi and art and math—it was a place to socialize, but in a zoo of more than a thousand kids, it was easy to get lost in the crowd.

After school we’d meet on the stairs in front of the block-wide three-story institutional building, and my friends and I would go to this cafe called Just Desserts down the street that had a back patio where we could hang out for however long we wanted to. I would buy a slice of lemon poppyseed cake and make eyes at this cute little punk girl named Silke, but I didn’t have a clue what to say to her. After sitting around there for an hour or two, we’d get bored and start to try to figure out where we could go and hang, or party, for the evening.

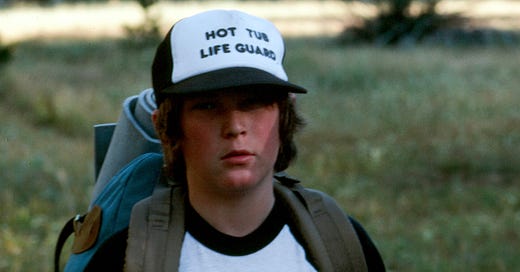

Especially since my hair was getting longer, I looked a few years older than I was, although ten or eleven plus three or four sure doesn’t get you anywhere near the legal drinking age. Even so, it was often me who volunteered to go try to get alcohol. I guess I felt like I had do something to earn my stripes.

I cruised back to the store on the corner right behind our school and posted up in front, waiting for an older stranger to come by. After an impatient few minutes, I figured, fuck it, I’ll just go in and try myself. I knew I’d be a hero if I could manage to “buy up” on my own. Holding my board in one hand by the front truck, I pushed through the swinging door and went straight to the beer fridge. I was already fascinated by all the varieties on display, and I stood there for a couple of minutes reading the labels. This was before the time of micro-breweries and craft beer, but there was already a wide range, including German beers like Becks and St Pauli Girl, Japanese imports like Sapporo, dark beers, light beers, Guinness, all sorts of stuff, and I was feeling the responsibility of choosing for all my friends, and for getting our money’s worth.

In the end, I knew the right call was whatever was cheapest. I pulled out a twelve-pack of Schaefer and went up to the front of the store, where the liquor was kept on shelves behind the counter. The friendly older woman smiled across at me as I stepped up, leaning my deck against the freezer case. Meeting her eyes for a second, I figured, be bold, act natural, don’t hesitate, and then I said the magic words for the first time—“How ‘bout a…fifth of Popov?” as I bent down to pull a cylinder of frozen orange juice out from next to the popsicles and It’s-It’s. She reached up for the plastic bottle and set it back on the counter in front of the register, next to the twelve pack. “Having a party?” she asked. “I looks like you might actually get away with this,” cackled the voice in my head, as I pulled out my money. “Yeah,” I said, keeping it casual, “a birthday party.” I handed her the cash and then stuffed my loot into my backpack along with my school notebook, swinging it over my shoulder as I went out the door.

* * *

The following year, we started to get our hands on grass and to hear of stronger drugs. I had a friend named James that I had met at summer camp who lived in Berkeley—and Berkeley was like a synonym for LSD in those days.

One afternoon I took the BART train over to meet up with my friend. He said he knew where to go, and so we walked down to Telegraph together, two twelve-year olds looking to score. I didn’t know what was supposed to happen, but, as it turns out, a big part of the answer to the question of how to buy drugs is that people who have them can tell if you are looking to buy them.

We must have had that look in our eyes, because before too long some dude approached us with his low key drug-dealer street patter—“Doses, doses, doses.” I looked up to take him in, along with the whole scene laid out behind this guy—ragged storefronts stapled-over with concert posters, greasy wax-paper pizza wrappers and cans in the gutter, people squatting on the stained concrete sidewalk, breathing the exhaust of cars idling at the stop signs.

I’d been all over the city of San Francisco already myself, and up to the end of Haight Street plenty of times to buy skateboard parts. This was a similar zone of hippies and drifters, but even more dirty and disorganized. Berkeley did carry some weight by way of its history, but it didn’t look good, and as a San Francisco native, anywhere outside the city was never going to be more than second rate anyhow.

Turning my attention back to the dude standing in front of us, I asked “Whatcha got?” “Purple gel. Hundred mics,” he said, opening his palm to show me a little paper envelope. He picked up the bindle and revealed a few tiny squares of what looked like colored gelatin. I glanced over at my friend, and he kinda shrugged and nodded back, so I dug into my cords and fished out a twenty that I’d earned doing computer programming after school, and the dealer handed me the gas. I think we ended up with something like ten hits. My buddy and I split, and I headed straight for the BART station on Shattuck to get back to the city ASAP—I wasn’t interested in sticking around over there.

Now that I had a source, I was the kid with the acid. I’d already realized that if I had alcohol or drugs, I was guaranteed to have friends—and not just other kids but cool, colorful, often older kids who didn’t follow the rules for their own sake. This habit of buying my way into relationships stuck with me for until sometime in my forties, when I finally realized that the answer to the question “Is it love, or money?” should be one or the other, and certainly not both.

The year I learned how to buy drugs on the street was the same year The Wall came out, and it often played as a double-feature with The Rocky Horror Picture Show, at the UC Theater back over in Berkeley. We’d all pile onto that same BART train that I’d taken to go score, and I’d hand out hits on the way, so that it would be coming on as we settled into our seats for the first movie. From downtown San Francisco, the train dips into a tunnel beneath the bay, and then emerges on the other side in a grey tangle of freeway overpasses and industrial waterfront, the wheels screeching as the tracks curve through Emeryville. We made this journey several times, watching the city recede into the distance across the water as we began to feel the acid kick in. Sitting on that train, waiting for our stop, it was impossible not to feel that we were in for a long ride.

And—let me just ask you, have seen The Wall? By now everyone knows that you want a tranquil, serene—and safe setting for a psychedelic experience, not something that does it’s best to conjure up a psychic war. It’s not even generally a great idea to drop acid and just go sit in a movie theater, let alone a movie like The Wall—and of course we weren’t just on acid, but acid and whatever booze we could get our hands on, as well. Ask your guidance counselor—LSD and alcohol are not a good combination. Mind-blurring downers and mind-opening stimulants—no, not a great mix—and keep in mind, that we were all still only twelve or thirteen years old at this point.

Those movie nights were both boring and terrifying. Sitting in a chair watching a screen at that age, fucking A, I wanted to be outside, running around, skateboarding, doing something and instead I was frying so hard I couldn’t see straight, the visual and auditory blast of the film combining with the hallucinatory effects of the drugs to produce not a peaceful sunny-day kaleidoscope of shimmering rainbow tracers and pixellated fractal starfields, but an all-out sensory assault. The Wall is one of the most accurate depictions of nightmare psychosis made on film, and it turns out that there isn’t much difference between psychosis and a bad trip. Relentless images of marching soldiers, screaming, twisted faces, and guns going off, accompanied by Pink Floyd’s bombastic, high-drama psychedelic soundtrack were all a bit much to sustain for two straight hours in the dark. When I wasn’t fidgeting, adjusting my cramped knees, and trying to catch the eyes of one of my friends with a silent look that might give them some idea of how much distress I was in, I was pinned to my seat, gripping the arms of the chair, my back and ass muscles clamped tight as I tried to remind myself that the ordeal would be over in a few hours—and wishing that it would be over even sooner.

At least Rocky Horror was more in the spirit of fun, although if you’ve ever seen it you’ll understand that it was its own kind of torture, made up of interminably repetitive sing-alongs of campy B-movie theme songs that plowed their own horror-show groove in my poor little head. “Let’s do the time warp”— for fuck’s sake, not again, please.

Looking back, I can’t actually conjure up any memory of fun on those movie nights, even though that was of course the idea of what we were all doing over there. I was going along because these were my friends—the ones I had earned—and I didn’t want to be left out. Let’s just say it was unpleasant at best, and really, it’s more accurate to say that I hated going to those double features.

Once in a while we’d be rescued by a parent willing to come fetch us with a station wagon at two in the morning—kind of them, but also—what the fuck were they thinking? Nobody asked what we were up to, as far as I know—and I do know now that if I picked up a handful of pre-teen kids at that hour and they were anywhere near as out there as we were, I would at least ask them what they had been up to. But no—no questions asked, I suppose in the spirit of 80’s free parenting, or…what? I still don’t know.

Thanks for reading, and for being part of this journey.

This is part of AN ORDINARY DISASTER, the book-length memoir about a man learning to listen to himself, and the price I paid until I learned how to do that, serialized right here on Substack with a new chapter published every week.

You can find everything from the memoir that I’ve published so far right here.

DECIDE NOTHING is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further reading

Here’s the table on contents for the memoir.

You might also enjoy some of my other work, such as

Why I Don't Use Psychedelics

I always thought of myself as a fan of altered states, but even as a lifelong drinker and early adopter of just about everything I could get my hands on, I noticed long ago that if the conversation turns to getting high, I lose interest after about twelve seconds. I think now that this is one of the first ways that my intuition tried to speak up about m…

or any of the other essays that you can find here

Eighteen essays about addiction, masculinity, creativity, and intuition

I recently divided my stack into sections—memoir, essays, mediations, and perhaps soon more—and in doing so I was reminded that I’ve put out no fewer than eighteen long form essays so far here, on topics ranging across anxiety, fitness, creativity, sobriety, self-discipline, purpose, love, adventure, sciatica, pain, AI, intuition, the collective unconsc…

What does this bring up for you?

Please share, comment, restack, recommend, and click the little ♡ heart right there 👇🏻 if you dig this piece. I’d love to hear from you!

Another great chapter Bowen.

There were some great lines and poignant observations that I really enjoyed. I also particularly like your view of the world/life - as in the things you notice and the way you interpret those things. I find it very unique and yet also somehow relatable.