Chapter 12 — Early days in the advertising-industrial complex, why nobody wants to pay for writing online, and why most conferences are so terrible.

An Ordinary Disaster — chapter 12 — Wired, Tired, Fired

When I look back at those last years of the nineties, it feels like a blur, and a binge. I was working the back half of what had unexpectedly become a first career in what had already started to be called “tech,” and it was starting to be clear to me that I wanted out. It was also true that I was still just in my twenties, and I wasn’t clear on much else, and I figured that I’d make the most of the ride while I could, especially since it was pretty clear that nobody was looking very closely at what I was doing. I liked feeling that I was getting away with something, and I took advantage of the ability to do so whenever I could, medium-wave surfing my corporate expense account with an constant excess of business travel, restaurant dining, drunken sex, and hotel high life, all of which felt like something while remaining entirely unfulfilling.

Strong cocktails were my drug of choice—Manhattans, at the time, in keeping with my frequent trips to New York, where I made sure to schedule morning meetings for no earlier than ten or eleven, so that I had plenty of time to clear my head with a double espresso from my favorite little East Village Brazilian coffee window, or, if I wasn’t already running behind, a lingering breakfast at Cafe Mogador.

I’d been hired in October of ’96 to write code and manage the team of programmers who built everything that the digital side of Wired created—a slew of high-design ‘content’ sites including magazine-quality features on everything from travel and cocktails to health and romance, a full-fledged daily news site, as well as HotBot, which along with sites like Yahoo, Altavista, Lycos, and Infoseek, was one of the most successful search engines before Google came along.

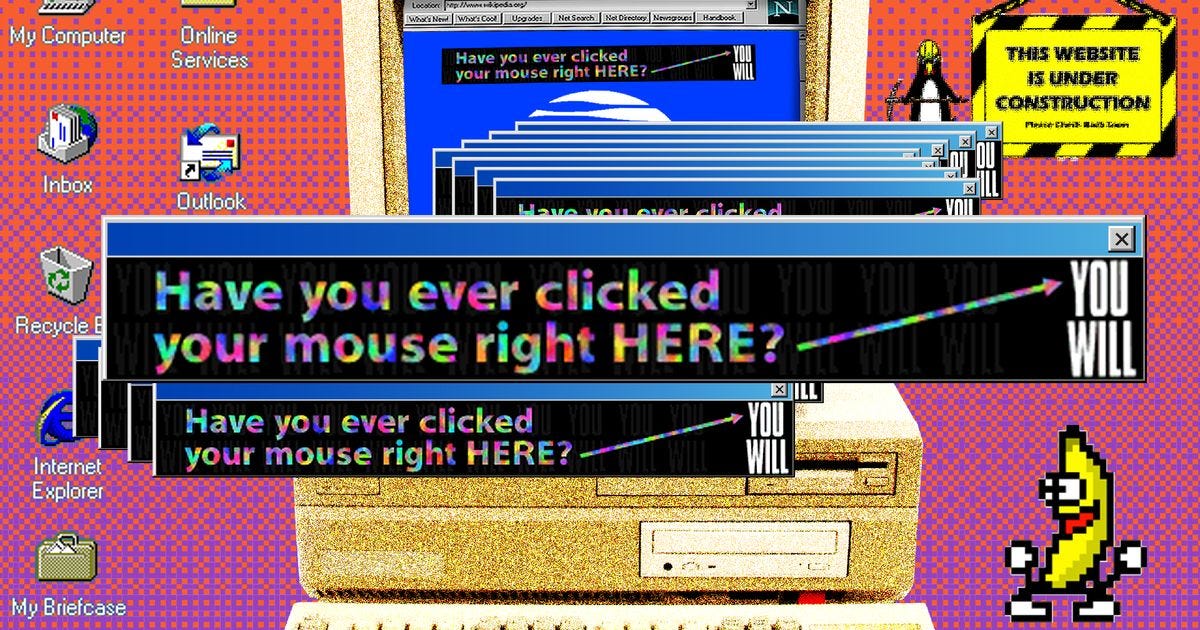

Keep in mind that this was still early days for the web, before any kind of app store, and although now we all subscribe to and pay for all sorts of things online—and anyone looking back from the present would likely assume this would have always been the case—the fact is that at that point, nobody wanted to pay for anything online, and it was impossible to do so.

As we were developing these sites in ’97, ’98 and ’99, I know that we talked about the idea of charging users directly to access what we were building, but the idea was quickly and categorically abandoned as both technically insurmountable and also fundamentally opposed to the ethos of the early web, which is often summed up by something that granddaddy Stewart Brand said in a 1984 conversation with Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple. Brand—now in his eighties and one of my neighbors here in Sausalito—is credited as having said that ‘information wants to be free’—pretty catchy, and also vague enough to mean almost anything at all.

It turns out that what Brand actually said was slightly different—that “information almost wants to be free,” and what he was getting at was that information was already tending towards being almost free, because the cost of distributing information via the internet was decreasing so fast that it was approaching zero. Said another way, the incremental cost of showing a web site to one more person is… just about nothing.

What he wasn’t saying was anything about the cost of creating web sites, nor about the value of information—neither of which, of course, are anything close to nothing. Computers and the internet do make it cheaper for more people to access—and create—information, but this truth got compounded along with Brand’s catch-phrase into what became the zeitgeist of those early days—the idea that, very broadly, everything on the web—even in the form of the highly articulated web sites that many of us were building, which of course required thousands of hours of work on the part of designers, software developers, journalists and many others—somehow ”wanted” to be “free,” and that users—that is, viewers, that is, people like you and me—thought those sites should actually be free to access, forever, without any payment at all.

The history and consequences of this rather tragic misdirection have been spelled out in much greater detail by many others, most notably researcher and writer Jaron Lanier, who details precisely how the whole clusterfuck evolved into the present-day phenomenon of surveillance capitalism, wherein we trade for the rather pathetically false offer of “free” access to whatever-whatever.com the willy-nilly accumulation of mountains of data about our purchases, our relationships, our bodies, and every other aspect of our selves for sale to advertisers who use that data to try to sell us things we would otherwise never discover any need or desire for.

Back in the day, what happened was that since we wished for information to appear to be ”free,” we had to find someone other than the consumer to pay for it to be created. Unlike those of us who thought we’d cooked up something entirely new, advertisers knew exactly how to take advantage of this new flavor of what was to them a very familiar media business model. They were ready to pay, and they did so happily, especially knowing that lacking any form of direct payment or subscriptions, they would have all the leverage as the only underwriters of our work as publishers. The result for me was that although I went to work at Wired because it seemed like a cutting edge place to be with a lot of intelligent people and interesting technical challenges, I ended up working in advertising—a word that I still have a hard time saying without making an ugly face or feeling an painful twist in my stomach.

If I’d been paying any attention at all to myself and my own values, I would have felt the disconnect much more strongly, but I wasn’t, and so I didn’t gave much thought to the fact that my income was increasingly derived from something that, at the very least, I didn’t have any affinity for. In fact, if I’d been more in touch with what I really thought, even then I would have said that I hated advertising, but I didn’t slow down long enough see the big picture. I needed to make a living, and I’d ended up a new niche that I could occupy without much competition. I’m sure I share the experience with many thousands of other folks who took tech jobs because they were intellectually stimulating, only to realize much later how that was outweighed by the degree to which they were even more spiritually compromising.

We’d deluded ourselves with this fantasy of ”free.” It sure sounded sweet, but it was a lie from the start, and, ever the pioneer, Wired was the first to pollute their high-design creations with over-bright ad “banners”—online billboards blinking their messages, all doing their damnedest to redirect your attention from whatever it was that you were really there for in the first place. For the most part, I had my head so deep in programming and servers and gigabytes of logs and reports that I didn’t allow myself to consider how much I was put off by all of that shit—and again, there still really wasn’t any alternative, because—believe it or not—nobody had figured out how to do online subscriptions yet. Back in the beginning, we’d ruled out direct micro-payments because every credit card charge incurs a fee of something like twenty-five cents, but it’s still a mystery to me why someone didn’t come up with the idea of subscriptions at that point. It sure would have saved us all a lot of pain.

As final proof that I’d ended up in a direction that didn’t agree with me, I turned down two job offers in those years that I worked hard to negotiate, and that would have been interesting, and incredibly lucrative. Part of me still wants to kick the rest of myself for turning down the money, but at least I knew enough at some unconscious level not to go even further down that road. I may have been into some rather seamy stuff myself, but that all happened behind closed doors. As has become all too clear since then, large-scale programmatic advertising has done far more damage to society—a much dirtier business really, even than smut.

The truth is that even as I’d found myself inside and part of the fascinating machine of early tech wonders, the whole thing was already starting to make me sick, but I wasn’t listening to these messages. Instead, I felt uneasy, and confused. I cooked up those opportunities, and then turned them down. I earned a big promotion, and then realized that I didn’t want that either. I wanted out, but I didn’t know what else to do. If only I’d combined my interests in geography and software to create something like… Google Maps—but that didn’t occur to me.

What I did have, however, was a strong inclination to seek out other people with whom I had something in common, and also to strike out for relatively empty territory. I wanted to be known, and to be known for being different. As the early cohort of digital media companies of that era began to grow larger—CNet, Yahoo, Excite, AltaVista, The New York Times—I began to discover that there were other people who were doing similar work at the fast-paced, toxic leading edge of online advertising technology.

I went to a couple of conferences—and saw very quickly how downright terrible they were. The rules and regs of industry trade associations were never my thing, and neither were trade shows focused on advertising, which were, very predictably, super gross. I remember showing up for something called Ad Tech at the Moscone Center in San Francisco around that time, and I lasted about forty-five minutes before I felt like I had to puke. It was packed—and to this day, I cannot for the life of me understand why anyone would want to subject themselves to such a greasy free-for-all of soulless sales-floor hustle. Empty-eyed men in ill-fitting khakis roamed the aisles of pipe-and-drape booths, the whole scene freckled here-and-there with women in leotards printed with company logos half-heartedly putting themselves through the motions of R-rated pole dancer routines in front of small clusters of clones in the same pleated beige pants.

Jesus Fucking Christ.

There was one conference that I went to that was totally different, however. WebMonsters was a semi-secret group of tech wizards with a silly name and a very serious mission. You had to be jumped in by an existing member to join, and the ethos much more like an academic conference. Everyone there was nominally a competitor, but came together in the spirit of mutual assistance, solving deep technical problems, and building the internet at large.

It took me only a little while after that experience to realize that I could use that same model to start a group of my own with a focus that matched my own work more closely. Anyone who’s been indoctrinated in the lingo of 21st century entrepreneurship will have heard—and it’s true—that the best reason for starting a business is to ‘solve your own problem’—that is, to fulfill a need or desire that you discover within yourself, for which the solution doesn’t already exist.

I didn’t learn that axiom until years later, but that is in fact exactly what I did. Over the next several months I managed to pull together the first meeting of what would become this thing called AdMonsters. Strangely enough, and very much contrary to the idea that you have to have a ‘business plan’ when you start a business, I hadn’t even thought of what I was doing as a business at that point. I just wanted to meet and talk with other people who were doing the kind of work that I was, and I wanted to do that in a context that was interesting, engaging, and actually worthwhile on a personal as well as a professional basis. I wanted it to be fun, and possibly even cool—instead of the sick-to-my-stomach feeling of alienation that stuck to me for days after going to other conferences.

I was still working at Wired when we pulled off the first meeting. Although at the very beginning I was just one of several co-organizers, somehow I emerged as the leader once we were there together, and the group coalesced around the ethos that crystallized years later as “focus, quality, community.“ We were all competitors, but only five or ten percent of what we did was proprietary, and because everyone in the room had the same role in managing this emerging “ad operations” function within one still-nascent digital media company or another—a role that most other people had little to no understanding of, or sympathy for, we all felt a huge sense of relief and gratitude in suddenly being part of a group of other people that got what we did for a living. It felt like community, because it was, and my focus on serving that community, and on honesty, openness, and mutual benefit became the foundation that carried the business forward for the next fifteen years.

Thanks for reading, and for being part of this journey.

This is part of AN ORDINARY DISASTER, the book-length memoir about a man learning to listen to himself, and the price I paid until I learned how to do that, serialized right here on Substack with a new chapter published every week.

You can find everything from the memoir that I’ve published so far right here.

DECIDE NOTHING is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further reading

Here’s the table on contents for the memoir. You might also enjoy some of my other work, such as

Advertising is Obsolete

I started a conference in 1999 called AdMonsters, during the last couple of years that I worked at HotWired/Wired Digital (the “digital” side of WIRED Magazine), where I was building big-at-the-time web back ends like the Hotbot search engine, along with systems to serve ads on top of those sites. Basically, I went looking for professional peers to talk…

or any of the other essays that you can find here

Eighteen essays about addiction, masculinity, creativity, and intuition

I recently divided my stack into sections—memoir, essays, mediations, and perhaps soon more—and in doing so I was reminded that I’ve put out no fewer than eighteen long form essays so far here, on topics ranging across anxiety, fitness, creativity, sobriety, self-discipline, purpose, love, adventure, sciatica, pain, AI, intuition, the collective unconsc…

What does this bring up for you?

Please share, comment, restack, recommend, and click the little ♡ heart right there 👇🏻 if you dig this piece. I’d love to hear from you!

Excellent article! I totally relate since I worked in for ad agencies from the late eighties until 2015. You are so right about the soul sucking nature of the ad biz. I worked on both sides of that fence in the print world and the digital and about the only thing I miss is the money, but even then the trade offs to get the money are too high, like working damn 18 hour days or longer.

I also relate to your experience at trade conferences. The worst for me though was attending any Google AdWords/ad seminars. I felt like I was the only one in the room who could recognize the absolute hamster wheel and blatant ad fraud of it all.

I'm with you. Good riddance to it all.

I remember a Tired/Wired from back then:

Tired: Banner ads on web sites

Wired: TV ads *for* web sites